|

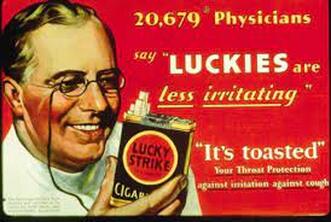

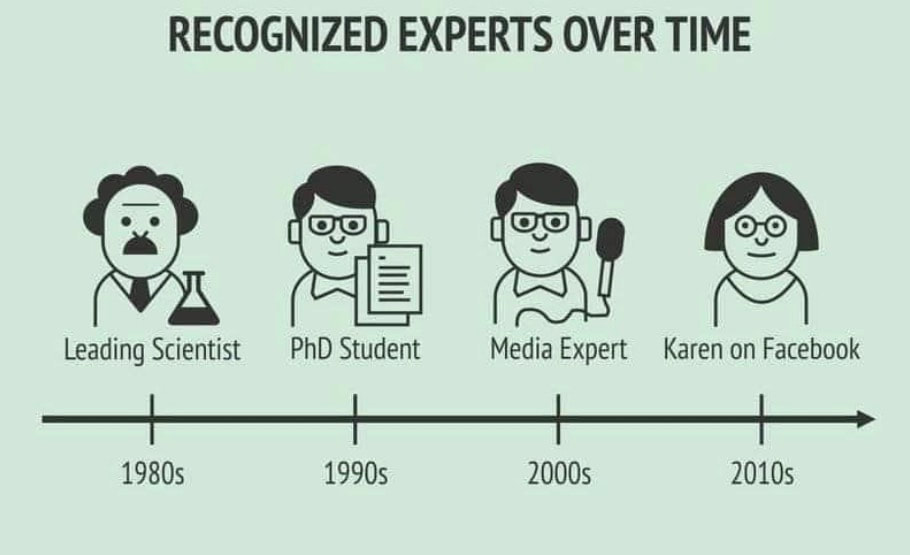

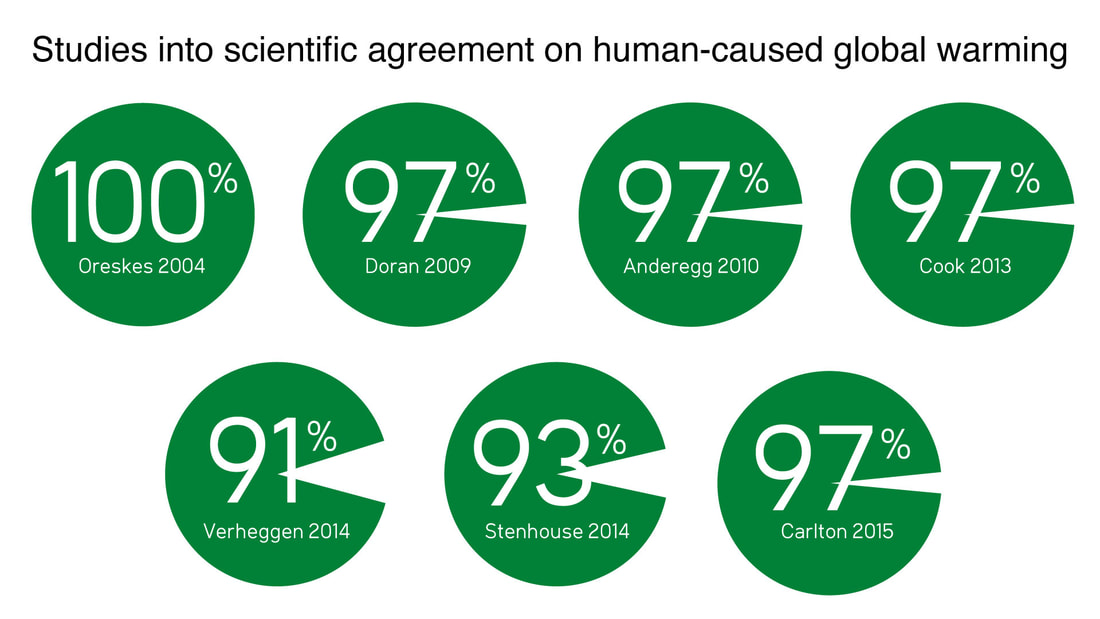

In the previous post, I discussed the importance of evidence and how scientists gather that evidence. We now examine the author. We are bombarded by the opinions of others. The rise of social media has allowed for much greater ability to share one’s views and opinions and to disseminate them. In many cases we can filter truth from fiction if we ourselves are fairly knowledgeable on the subject. Most of us would ignore the ramblings of those who believe in a flat earth, but what if you are not completely conversant on the topic? Add to the fact that many of the more ‘discussed’ issues, such as climate change, are quite complex, at best, we have only a superficial understanding of the topics. So we therefore rely on the authority of the author of the information. So how are we to assess if the author is qualified on the subject at hand? The author or presenter of the information received must meet certain criteria if we are to judge the veracity of the information they give. 1. They must be experts in the field of discussion. Clearly we would not accept an opinion delivered by a blogger who knows little about how science works, let alone medicine, when discussing medical treatments. Take for example Gwyneth Paltrow or Peter Evans who talk about food that “detoxes” you when we have a perfectly good set of kidneys and a liver that that do the job. But what about a person who is a doctor? They may know about their field but not necessarily about another. Would you trust a person with a PhD to give good advice about specific medicines, if their field is education? I think not. Nor would you implicitly trust a medical doctor to provide advice on engineering matters. Unfortunately many ‘communicators of opinion’ use their titles to their advantage to persuade their readers. For example, you may read from certain scientists who have reservations on climate change or vaccination, when a little research shows that their expertise is neither in climate science nor immunology.  2. Authors need to be free from biases. In the 1950’s many doctors and scientists argued that smoking wasn’t that bad. Ignore the fact that they were paid by tobacco companies to say that. In this case they were paid to promote smoking, and thus benefited from the promotion. It introduced a bias in their opinion. However, it can be more subtle. Energy Research Institutes may talk about clean coal, when closer inspection shows that contributors to their research includes mining companies and oil companies. So when we examine the authors’ credentials, we also need to examine any links to things that may result in bias. It doesn’t mean we outright reject their statements, but it does cast concern that needs to be considered. 3. You need accuracy. But what is meant by accuracy? Like the evidence, that means you need a lot of scientists saying the same thing.To explain, let’s look at an example. Say you have an illness and are unsure of the best course of action. You see your doctor who says, “You only need bed rest.” You are unsure, so you seek a second opinion, and they say, “you need to take this medication but you may have some side effects.” But you are still unsure. So you see 10 more doctors, who all say you should take the medication. What will you choose? The fact that 10 more doctors agree should lead you to follow their opinion. Similarly in science, a research paper may make a particular claim. Further research shows that there are 100’s of other papers which agree with that claim, whereas only 2-3 which don’t. Irrespective of the qualifications of the authors that disagree, and they may have adequate knowledge of the subject, the fact that there are few in number, should be pause for concern. 4. Lastly, the ‘age’ of the authors' statements need to be considered.

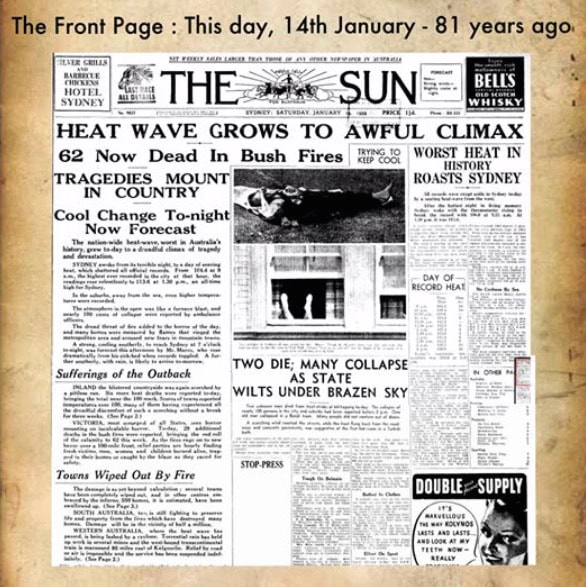

If a paper makes certain conclusions in a paper that was written a long time ago, and new evidence comes to light that contradicts that conclusion, then the original conclusions may not be correct. Sometimes the time delay may not be long. During the COVID pandemic, mask wearing was not particularly encouraged at the start of the outbreak by health authorities. But as scientific evidence poured in that showed its benefit, the health authorities strongly encouraged mask wearing and governments started mandating it. The point is: as evidence becomes available, old conclusions may become invalid and this should not be relied upon. As a result, researchers and students are encouraged to ensure they research papers that are recent, that is, less the 10 years old So in summary, when researching a certain claim, ensure that the author has the qualifications, are free from bias, and that their views are supported widely in the scientific community. My third installment will examine how science is communicated and often miscommunicated

1 Comment

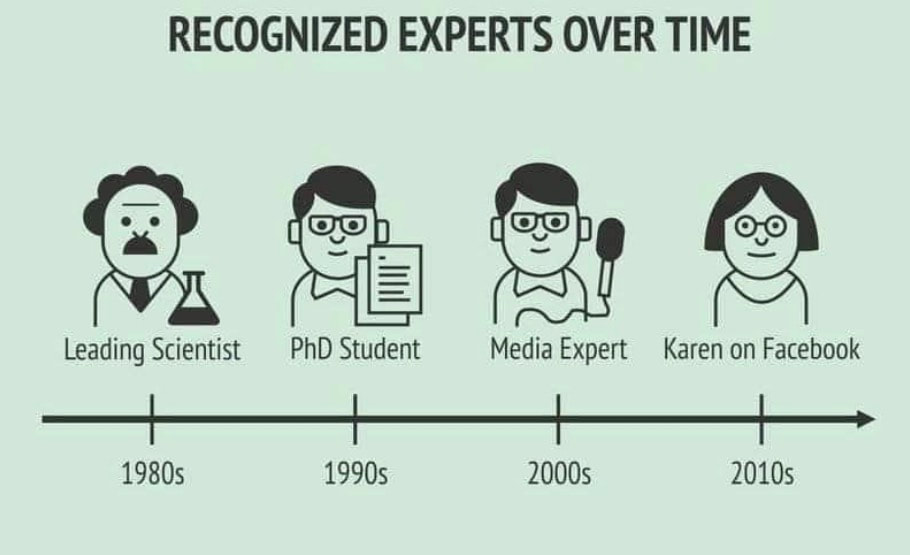

We are bombarded with information. Traditionally this has been through print media, such as books and newspapers, and audiovisual through the medium of television. However, in the last 25 years, the exponential growth of the internet has resulted not only in a huge increase in the amount of information, but it has also increased the number of sources of information. Prior to the internet, most of our sources of information came from vetted sources, such as journalists and experts in their field. With the advent of the internet, and social media, anyone can now express their opinions and views, increasing the number of ‘voices we hear’. Many of these lack the necessary knowledge of expertise and qualifications. The recent challenges of climate change, COVID, and subsequently the vaccinations have shown how powerful many of those voices have become. With many claiming to ‘have the truth’, how do we know what is the truth? How do we separate fact from fiction? How do we assess the claims made? There are three key principles to consider when evaluating claims

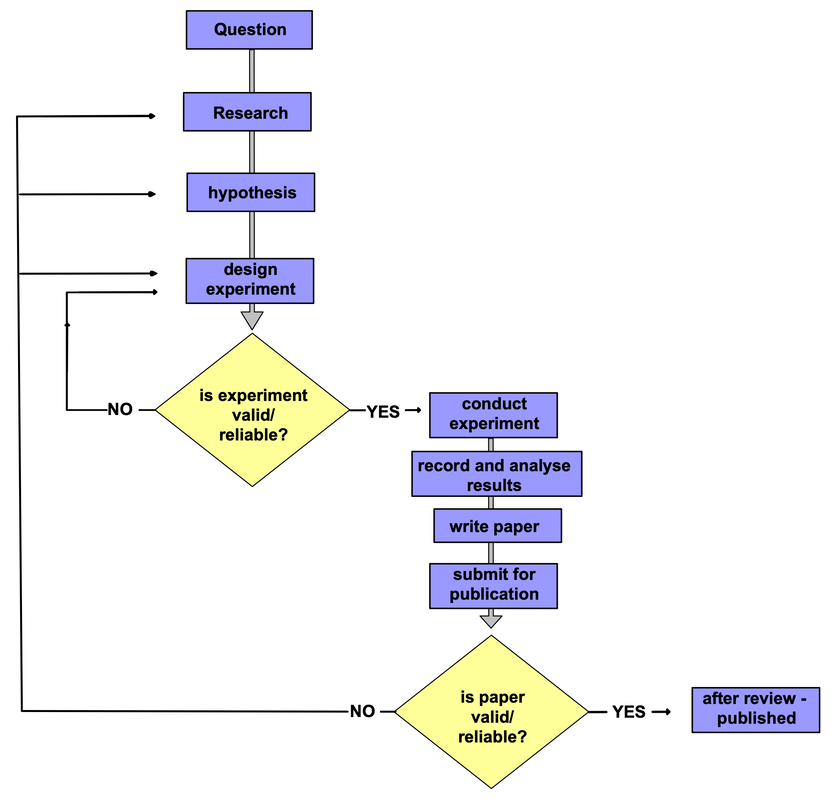

Over a series of three blogs, I’ll address these principles, and in the process hope to give insight on how science works.  The Evidence No matter which side of the debate you are on, evidence reigns supreme, but what evidence, scientifically speaking? Evidence is data driven scientific work, that is, - data is collected, and lots of it, - correlations are drawn between different variables, and - models are developed that attempt to explain the connections. As more data is collected those models are tested, modified if necessary, and at times, the models change if the evidence (read ‘data’) does not fit the model. What is important is how the evidence is collected, since it is imperative that - the data is reliable - the data is consistent with multiple measurement taken - and valid - the data is free from things that could skew the results, such as bias, incorrect methodologies, or other variables that are not taken into account. Within science, there are very strict processes scientists use to ensure their data is reliable and valid. An overview of the scientific method 1. Scientists design their research (whether it by experiments, or data collection, for example) with the proviso that what they are looking for is not true. In essence, scientists try to disprove things, rather than ‘prove’ them right. For example, a scientist may want to investigate whether certain foods lead to increased heart disease. They will design their experimental work to show that that there is no link! Why? Because of confirmation bias. If you set out to look for evidence that supports your idea (in Science that is called a hypothesis) , then you stand the risk of seeing trends in the data that support your idea, when it actually does not.

The higher the number of samples taken, and if they are consistent, the more reliable the data. So when doctors say there is a strong link between smoking and lung disease, we take this seriously because it’s based on a huge amount of data collected, millions of people in close to 10,000 research papers. 3. When scientists design experiments, they often compare the data to a ‘standard.’ This is referred to as a control.

An example will help. A scientist wishes to test a drug for a heart disease. They will examine many patients (to ensure reliability). They give the drug to one group and then to another group, they may give something that looks like the drug, but actually contains no active ingredients, (called a ‘placebo’) When they get the results, they compare the two groups. You will very rarely get a super clear delineation (such as, all the people who received the drug improved, whereas all the placebo group did not). You will get some overlap; there will be some who received the drug but for whatever reason, did not improve. Similarly you might find that some in the placebo group improved. But if a VAST majority do improve with the drug, then there is a strong link to the drug and improvement. 4. The next step is to communicate the results, and researchers will then communicate their results by writing a paper and drawing conclusions. They will rarely speak in absolutes (“the drug definitely works”). Rather, they will be cautious. They understand that, as with any research, more evidence is better. So they may conclude, for example, ”People on Drug A showed a 25% improvement compared to a placebo” 5. Finally, the researchers will submit their work (or paper) for publication in a reputable journal. Is that it? No. The journal will review the paper, drawing on the expertise of other scientists in the field to critically examine the paper. If that passes the evaluation, the paper is published. Once published, other researchers can try to repeat the work, and will publish papers supporting the work, or critiquing the work, if they collect data that does not support the original paper. This is what is meant by a paper that is peer reviewed. It has gone through a very lengthy and comprehensive process to ensure that the data collected is done well and the conclusions drawn are appropriate and free from bias. As you can see, the process is rigorous to ensure the evidence collected is reliable and valid. So when you read online (or elsewhere) about some claim it is very important that any mentioning of evidence is backed up by quoting the actual research, that is, peer reviewed papers , which means it is data driven. It is not enough to say that evidence exists without actually quoting the actual research. In that case, it is just an opinion. In the next post we will examine the source of information, who is the author and whether they have the credentials for the information., so subscribe I recently had an experience that hit home the concern of new teachers leaving the profession.

I spoke with a new teacher who had only graduated at the end of last year. Let’s call her Lisa. By all accounts she was a capable new teacher, knew her content well, delivered engaging lessons to her students, was willing to learn herself, and important, passionate about wanting to teach and motivate students to science. And, last year, I was excited to hear that a local well known school with a strong reputation was considering her employment. When I met her again last week, I discovered she had left the profession. She was burnt out. What happened? The school placement fell through and instead got employment at another school. This school has its challenges especially where it is socio-economically, and I am sure there are dedicated teachers there. However, Lisa’s experiences were far from supportive. She arrived discovering that each teacher was working on their own unit of work, there was no collaboration in producing programs across each year. More alarmingly, when Lisa asked to see the programs, she was told that there was no sharing, she had to do it all on her own. When she had classroom management issues (we will all have them) she got no support from her immediate supervisors. She was left to fend for herself. To me the attitude she was facing was akin to a parent telling a toddler , “get your own food, I’m busy and I font's care”. Thus it isn't that surprising she started getting panic attacks, and eventually left. This resonated with me, as I had a very similar experience in my early career. I don't think this isolated. Recently , I heard a similar story from a more experienced teacher who was also placed in another school, who got no support from her faculty, especially with dealing with student issues, from the faculty head no less. Studies seem to suggest the attrition rates for new teachers can be as high as 25% in the first 5 years and a Commonwealth Study from 2014 found 5.7% teachers leave in any given year - see the link below for further details. I appreciate the fact that teachers leave for a variety of reasons, misplaced expectations, changes in circumstances, other professional opportunities, but high on the reasons provided in studies is a lack of support. Being based in NSW, Australia, I refer to the the Department of Education and Training (DET) and DET do have policies in place to support new teachers. But I am concerned that possibly these polices aren't always enacted on. Add to the fact that many new teachers, especially in government schools, are placed in schools that have a high turnover rate - schools in disadvantaged areas, schools that are remote, or both. Yet, these are the places that need experienced teachers to effective teach in challenging circumstances. I acknowledge I am no expert in understanding the complexities of the reasons behind the teacher attrition, but as a science educator I am especially cognisant of the need of effective science communicators to advance a passion for science and grow a scientific literacy in our community. And when we see good science educators leave because they get no support, we all lose. Please add to the conversation - experiences, thoughts, ideas

....Well, finally started my first blog. My hope is that this will be a repository of my musing on science education, not just physics, but other topical issues in the news where science communication is key. Other topics will include the state of science education, and share ideas to better communicate science, not only in the classroom but beyond as well So here is my first musings...(and they are meant to be musings to promote discussion so are not too tightly edited) I have just completed a series of three videos on evidence for climate change. (You can find them on my YT channel) One of the main drivers for this topic has been my frustration at seeing climate deniers on social media, post things such these... What's frustrating is the cherry picking involved and the often the unwillingness to look at the evidence properly. And it seems that climate deniers have a poor understanding of the process of science. (I call them climate deniers not sceptics because science relies on scepticism. True scientific skepticism is where they challenge the prevailing views, look at the evidence and change their views accordingly.) Science works on the principle where "evidence trumps opinion". Unfortunately much of what what I see about climate denial, is the complete reverse! (and I am sure many of you would see the same in other areas as well, where opinion trumps evidence.) A friend posted this picture recently and it captures this well... Apart from vested interests, I think one of the main contributors is the poor scientific literacy.

Educational researchers have in recent decades bemoaned the data that shows an uptake in science, both in high school and in higher institutions, had steadily decreased. There are many reasons suggested for this, and I am not going into it now - that would be a loooong discussion - but I do want to highlight one. In a world, of instant this and instant that, there is a decreasing trend of critical thinking. There is an unwillingness to have 'considered views', one where one needs to take time to look, time to think. Science relies open that. There is no quick soundbite. It takes time - collecting data, analysing data, thinking through the implications. It's easy to teach science as facts, but that's not what science is. Teaching the process of science is much harder challenge There are many fine teachers who are working very hard to teach science well, but are finding it a challenge to teach students to be critical thinkers in an age of instant information. The result: more ill-informed opinion being presented as fact, when the evidence isn't there. What do you think is the reason behind this rise is climate denial? What do you think needs to happen to address the scientific illiteracy? Leave your comments below (You may need to click on the title above) |

AuthorTeacher, YouTuber, Archives

November 2021

Categories

All

|

|

© COPYRIGHT 2024.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed